Lung cancer: key points

- Lung cancer most often develops from bronchial cells. There are two main types of lung cancers: non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer. They represent approximately 80% and 20% of cancers, respectively.

- Three types of treatment are used in the treatment of lung cancers: surgery, radiotherapy and medical treatments (chemotherapy and targeted therapies).

- The choice of treatments is adapted to your situation. Several different specialty doctors meet to discuss possible treatment options for you. They are based on recommendations of good practice. They can also suggest you participate in a clinical trial.

- For non-small cell lung cancers, surgery is the standard of care when your general state of health allows it.

- For bronchial small cell cancers, chemotherapy, whether or not associated with radiotherapy, depending on the stage, is the reference treatment.

- The team that supports you includes professionals from different specialties: a pulmonologist, medical oncologist, surgeon, radiation oncologist, psychiatrist and psychologist, pain specialist, nurse, physiotherapist, caregiver, dietician, social assistant … These professionals work in collaboration with the health facility in which you receive your treatments and in connection with your doctor.

- Treatments can cause side effects that are also subject to medical care. Practical tips can also help you mitigate them.

- The management of cancer is comprehensive and includes all the care and support you may need from diagnosis, during and after treatment: psychological support, social support, pain management, etc.

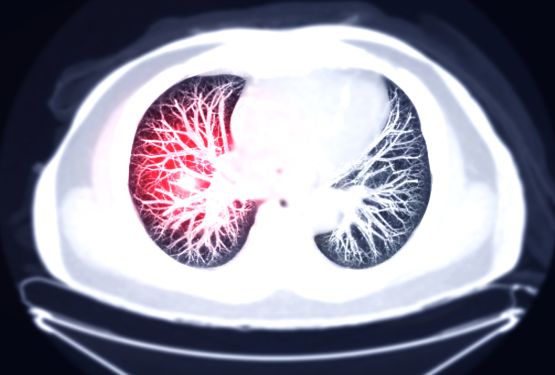

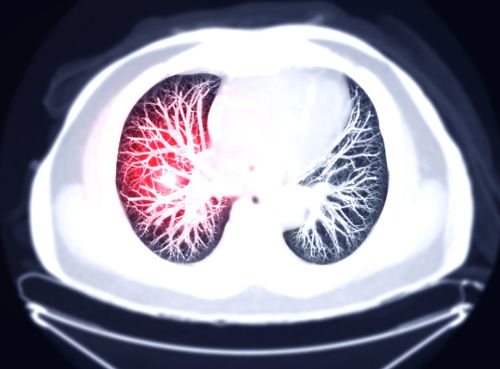

Anatomy of the lungs

Our respiratory system consists of nasal passages, trachea and two lungs. Its role is twofold: to supply our organism with oxygen (O2) and to evacuate carbon dioxide (Co2).

The lungs are located in the chest, on each side of the heart. They are divided into several lobes, themselves divided into several segments. The left lung has two lobes and the right lung has three lobes separated from each other by partitions called scissures. Each lobe contains the bronchi. The bronchi consist of alveoli (small pockets) connected to each other by the bronchioles. All bronchi are connected to the trachea.

During a breath, the air comes through the trachea and is distributed in the bronchi, then the bronchioles and alveoli. The oxygen contained in the inhaled air circulates in the alveoli. It crosses their wall to go to the blood. The blood then distributes oxygen to all the cells in the body.

At the same time, in the opposite direction, the carbon dioxide released by all the cells of the body passes into the blood. Carbon dioxide passes through the alveoli and then passes through the bronchi. It goes away through the trachea, then the nose and mouth. It’s exhalation.

A double envelope (the pleura) keeps the lungs against the chest wall. The bronchi are lined with a protective layer of mucus. The cells of the bronchi have on their surface very thin cilia, which, like a broom, continually push the mucus towards the trachea by eliminating the inhaled particles. When the amount of mucus is significant, it produces sputum.

Between the two lungs, above the heart, there is the region of the mediastinum that extends from front to back of the sternum to the spine. The mediastinum contains large blood vessels such as the aorta, trachea, and esophagus. It also includes the mediastinal lymph nodes, located behind the sternum.

These lymph nodes are part of the lymphatic system whose role is to evacuate the waste emitted by the body (including those coming from the lungs) via a liquid, the lymph. Mediastinal lymph nodes can be reached by cancer cells.

Lung tumors

The lung can be the site of benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous) tumors. The major difference between benign and malignant tumors is the inability of the former to migrate to other parts of the body (metastases).

Of the malignant tumors that can affect the lungs, some are called primitive when they originate in the lung. Others are called secondary when they have spread to the lung from another organ. Secondary tumors are called metastases. For example, you may be suffering from pulmonary metastases of primary cancer of the breast.

Benign tumors

Benign tumors account for 5 to 10% of all tumors that affect the lungs. They usually do not cause major health problems.

However, a tumor that develops in a bronchus and blocks it can lead to consequences of varying severity, such as pneumonia, bloody sputum (hemoptysis), or collapse of a lung (also called atelectasis), related to the decrease of the air entering at the moment of breath.

There are several forms of benign tumors.

Malignant tumors

A malignant tumor is a mass of cancer cells that can spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body.

Cancer cells also have the distinction of multiplying rapidly and infinitely. Lung cancers mainly originate in the cells of the bronchi but they can also be born from the cells that cover the pulmonary alveoli. 95% of lung tumors belong to one of two families:

- Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

- Small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

These two types of lung cancers are derived from bronchial cells of different origins. When cancer cells of each type are observed under the microscope, they do not have the same appearance. It is the difference in appearance that has led to the classification into “small cell cancers” and “non-small cell” cancers. These two cell types behave very differently in cancer progression and in their sensitivity to treatment, hence the importance of distinguishing them during diagnosis.

There are other types of rare lung malignancies including sarcoma and lymphoma.

Pulmonary metastases

Lung metastases are formed when cancer spreads to the lung from its original location in another part of the body.

The lung is a frequent focus of metastases that can be derived from other primary cancers such as breast cancer for example. The cells migrate from one part of the body to another organ through the blood and lymphatic system.

Lung Cancer Risk factors

The role of a number of risk factors in the occurrence of lung cancer has been proven.

Tobacco is the number one risk factor for this cancer. Its role has not only been highlighted by epidemiological studies. Its carcinogenic effect has also been highlighted by research in molecular biology.

Other factors are suspected to have an influence on the development of lung cancer, however, their impacts have not been formally identified so far.

- Tobacco

- Occupational exposure

- Other risk factors

- Risk reduction

Thanks to scientific studies, we now know better certain mechanisms of cancer development.

However, it remains difficult to accurately determine all the causes of cancer. There are very few cancers for which a single cause is recognized.

Scientific studies have investigated whether the development of lung cancer can be promoted by characteristics specific to the individual types of behavior and lifestyle.

These are called “risk factors”.

Any condition, or substance, that increases the risk of cancer is a risk factor.

Most cancers appear to be the result of a complex set of many risk factors, including heredity, lifestyle choices, and exposure to cancer-causing substances (carcinogens) in the environment.

In general, the greater the intensity and duration of exposure to a risk factor, the greater the probability of being reached. But:

- The development of cancer after exposure to a risk factor can extend for years

- You may be exposed to several risk factors during daily activities

This is why the search for risk factors does not always make it possible to determine the origin of lung cancer.

Some risk factors are related to behaviors and can be avoided. Others are said to be “constitutional” (such as age, genetic factors) and cannot always be acted on. A person who has one or more risk factors may never have lung cancer. Conversely, a person with no risk factor may have lung cancer.

Symptoms of lung cancer

The symptoms of lung cancer are not specific to this disease, that is, they can be caused by other diseases.

If any of the following symptoms persist, it is important to consult your doctor and have a check-up, especially if you smoke or have smoked (even if you have stopped smoking for many years).

Frequent symptoms

Some symptoms occur among about one in two patients and are considered frequent. They combine respiratory problems and a modified general physical condition including:

- The appearance of a cough or the increase of a cough of chronic bronchitis

- Acute or chronic severe pain (such as a sore point evoking a muscle tear, rheumatism-like shoulder pain)

- The onset or worsening of shortness of breath, in the absence of proven heart problems

- Hemoptysis

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Repeated pulmonary infections (bronchitis or pneumonia)

- Unusual and persistent fatigue

Other symptoms

A change in voice or persistent voice loss related to the compression of one of the nerves involved in the operation of the vocal cords. We talk about dysphonia.

Wheezing caused by compression of the trachea and large bronchi. This phenomenon is also called wheezing,

Difficulty swallowing in connection with the compression of the esophagus (dysphagia),

Difficulty breathing due to the presence of fluid in the pleural cavity that contains the lungs (pleurisy) or the presence of stagnant fluid between the 2 layers of the pericardium, the membrane that surrounds the heart (pericarditis).

A set of manifestations with swelling of the face and neck, headaches, visible veins on the upper part of the thorax. The compression of the superior vena cava is involved. This is the “superior cave compression syndrome”.

During lung cancer, especially during SCLC, physical manifestations can develop indirectly outside the lung. These symptoms are grouped under the name of “paraneoplastic syndromes”.

What is the diagnosis?

Diagnosis is the process of identifying a disease based on its signs.

A diagnosis of cancer always requires the examination of tissues taken by biopsy in a suspected area. This tissue is examined under the microscope, and it’s called a pathological examination. It is essential to confirm the presence of cancer and to determine its type.

The diagnostic procedure has two phases: the diagnostic assessment and the extension assessment. Examinations are usually done in a typical order, which may vary.

The diagnostic approach allows to:

- Confirm the presence of cancer

- Identify the type of cancer

- Find the location where cancer originated (the primary tumor)

- Have an idea of the extent or spread of cancer (stage)

- Develop a treatment plan

In the case of a suspicion of lung cancer, the prescribed examinations are also aimed at determining whether the tumor is resectable (that is to say if it can be removed, in particular, according to the extent of the disease). And if the patient is operable (that is to say, verify that his state of health authorizes the intervention with, in particular, the evaluation of his respiratory function).

Diagnostic balance sheet

This assessment includes:

- A clinical examination performed by the doctor who assesses the general condition of the patient

- A chest x-ray

- A chest CT scan with upper abdominal sections (also called computed tomography)

- Bronchoscopy during which samples are taken (biopsies)

It can happen that the samples taken during bronchoscopy do not allow making a diagnosis. In this case, other samples can be taken:

- Fine needle aspiration biopsy under scanner performed through the skin (trans-parietal)

- Biopsies performed during mediastinoscopy or thoracoscopy

- Biopsies of metastases

Extending balance sheet

A number of examinations are prescribed to determine if and where the lung cancer has spread (i.e. its stage):

- A thoracic CT scan with iodine injection and upper abdominal sections, to discover possible pulmonary metastases, intrathoracic, hepatic or adrenal lymph nodes

- CT scan or brain MRI

Stages of non-small cell cancers

The most widely used non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) staging system is the 2009 TNM classification.

- The TNM classification

- Primary tumor (T)

- Regional lymph nodes (N)

- Remote metastasis (M)

- Stage grouping for NSCLC

TNM classification

TNM stands for “Tumor, Nodes, Metastasis”.

The TNM classification takes into account:

- the size and location of the primary tumor

- the number and size of regional lymph nodes that contain cancer cells

- The spread of cancer or metastases to another part of the body

A primitive tumor (t)

- TX

The tumor cannot be evaluated or is demonstrated by the presence of malignant cells in the sputum or bronchial lavage without visualization of the tumor by endoscopic or imaging examinations.

- T0

No evidence of primary tumor (i.e. no tumor).

- T1

Tumor 3 cm or less in its largest dimension, surrounded by the lung or visceral pleura without bronchoscopic evidence of more proximal invasion (i.e. closer to the center of the lung) than the lobar bronchial.

- T1a

Tumor of 2 cm or less in its largest dimension.

- T1b

Tumor of more than 2 cm without exceeding 3 cm in its largest dimension.

- T2

Tumor of more than 3 cm without exceeding 7 cm in its largest dimension or having any of the following characteristics:

– attack of the bronchial stump at 2 cm or more from the carina (the point where the trachea is divided into left and right bronchial tubes).

– invasion of the visceral pleura (the membrane which covers the entire surface of the lung).

– atelectasis or obstructive pulmonary disease extending to the hilar region without reaching the entire lung (i.e., partial obstruction of the airway total collapse of the lung).

- T2a

Tumor of more than 3 cm without exceeding 5 cm in its largest dimension.

- T2b

Tumor of more than 5 cm without exceeding 7 cm in its largest dimension.

- T3

Tumor over 7 cm:

– Or directly invading one of the following structures: the chest wall (including in the case of the Pancoast tumor), the diaphragm, the phrenic nerve, the mediastinal, pleural or parietal pleura or the pericardium.

– Or a tumor in the stem bronchus within 2 cm of the hull without invading it.

– Or associated with atelectasis or obstructive pulmonary disease of the whole lung (i.e., total collapse of the lung).

– Or the presence of a distinct tumor nodule in the same lobe.

- T4

Tumor of any size:

– directly invading one of the following structures: mediastinum, heart, large vessels, trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve, esophagus, vertebral body, carina.

– or the presence of a distinct tumor nodule in another lobe of the affected lung.

Stages of small cell cancers

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is still often classified into two stages that designate degrees of disease extension. The choice of treatments is adapted to the stage of the disease.

Localized stage

The disease is localized when the tumor is presented only in the thorax and the cancer is observed in a single lung, the mediastinum (tissues between the lungs) and the adjacent lymph nodes (hilar and mediastinal ipsilateral and contralateral, ipsilateral colloidal).

Disseminated or metastatic stage

The disease is disseminated, metastatic or spreads when cancer has spread to the other lung, to the lymph nodes on the other side, chest or other parts of the body, especially outside the chest.

Treatments

Three types of treatments can be proposed for the management of lung cancer: surgery, radiotherapy and medical treatments by drugs (chemotherapy or targeted therapies). They can be prescribed alone or be associated with each other.

- Thoracic surgery

- Thoracic radiotherapy

- Chemotherapy

- Targeted therapies

The management of lung cancer thus often combines locoregional treatments and systemic treatments:

- Locoregional treatments (surgery, radiotherapy) attack the tumor and treat the surrounding area.

- Systemic treatments are medications (chemotherapy, targeted therapies) that circulate throughout the body and act on cancer cells wherever they are located.

If radiotherapy and chemotherapy are offered after the surgery, they are called adjuvants, which means that they come to complete it. In this case, radiotherapy or postoperative chemotherapy are also mentioned.

If they precede the surgical procedure, they are called neoadjuvant or preoperative.

The symptoms caused by the presence of lung cancer are also supported, in parallel with the treatment of the tumor.

Patients may be prescribed different treatments depending on their situation.

The medical file of each patient, made up of the different examinations carried out during the diagnostic and extension tests, is discussed in a multidisciplinary consultation meeting (RCP).

At the end of this meeting is established a personalized program of care (POC). This document sets out the protocol of care that is recommended by practitioners, based on good practice recommendations. This POC is presented and discussed with the patient.

The choice of the treatment proposal, discussed by the medical team in a multidisciplinary consultation meeting, is done by taking into account a certain number of criteria:

- The age of the patient (being older than 70 is not a contraindication to intensive treatment)

- His general condition (measured in particular by the performance score or the Karnofsky index)

- Other diseases (co-morbidities) of the patient and the associated treatments

- Cancer: its type, its form, its stage, the degree of extension of the disease.

Although the choice of treatments is made according to all these elements, the treatment options are often presented in stages.

Thoracic surgery

There are several types and techniques of surgical resections.

The goal of the surgery is to perform complete resection – removal of the tumor. This is called “radical” intervention, the aim of which is curative.

There are two main types of interventions:

- Lobectomy: The surgeon removes a lobe from the lung.

- Pneumonectomy: One of the two lungs is removed completely.

These gestures are always accompanied by ablation of the neighboring ganglia (ganglionic dissection).

Depending on the patient’s situation, surgeons may use other types of procedures, but more rarely.

Surgery is the gold standard treatment for stage I, II non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). After discussion in CPR, it can be used for stages IIIA and exceptionally proposed for stage IIIB.

Surgery is exceptional in the management of small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

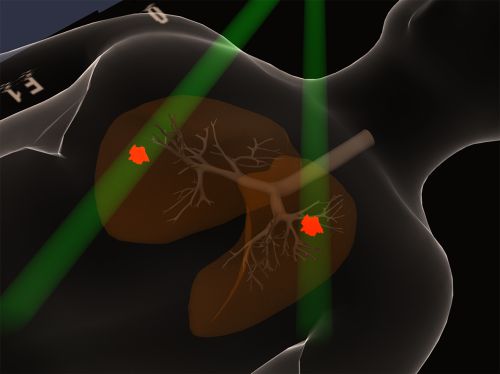

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses rays or high-energy particles to destroy cancer cells.

As part of the management of lung cancer, external radiotherapy in the chest is intended to irradiate the tumor and its periphery and the locoregional ganglia.

In the case of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the possible indications for radiotherapy are as follows:

- reference treatment, combined with chemotherapy (concomitant chemoradiotherapy, i.e. one or more chemotherapy molecules are injected in parallel with radiotherapy) for stage IIIB cancers

- discussed in SPC as part of multimodal therapy (i.e. combining several therapies) for IIIA stages

- as an alternative to surgery in case of the unresectable tumor (i.e., when the tumor cannot be removed) or non-operability of the patient for stage IA and IB cancers

- in addition to surgery and chemotherapy for parietal involvement (when the tumor reaches the lung wall) or incomplete excision (when the tumor could not be removed in its entirety) for stage II cancers,

- for treatment of metastases (brain irradiation, bone …).

In the case of localized small cell lung cancer (SCLC), radiation therapy usually associated with chemotherapy (concomitant chemoradiotherapy) is the standard treatment.

In the case of small cell cancers, prophylactic brain irradiation (i.e., preventive localized radiation therapy) is recommended in response to initial therapy (i.e., chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy treatments have been effective).

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs that are toxic to cells, which act on the mechanisms of cell division to destroy cancer cells.

The chemotherapy molecules can be administered by the venous route (as an infusion) and/or orally (as tablets or capsules).

In the case of lung cancer, commonly used chemotherapeutic agents are cisplatin (in injection) or more rarely carboplatin (in injection). These molecules are always associated with other drugs. We can mention among others:

- Etoposide (in injection or capsule)

- Paclitaxel (in injection)

- Docetaxel (in injection)

- Gemcitabine (in injection)

- Vinorelbine (in injection or capsule)

- Pemetrexed (in injection)

These molecules can be marketed under different names.

These molecules have different toxicities and therefore specific side effects.

In the case of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the general indications for chemotherapy are as follows:

- Discussed for certain IB stages

- Recommended as adjuvant (after surgery) in stages II

- Recommended for multi-modal (i.e. multi-treatment) treatment in IIIA stages,

- In combination with radiotherapy (concomitant chemoradiotherapy) in stages IIIB

- Reference treatment of stages IV

For small cell lung cancer (SCLC), it is usually indicated:

- In combination with radiotherapy for localized forms

- As a reference treatment for disseminated forms

Targeted therapies

Unlike conventional chemotherapy molecules that act on all dividing cells, targeted therapies block a growth mechanism specific to cancer cells. This results in less toxicity for the other cells of the body. However, these treatments are not devoid of side effects. Three molecules currently have a “marketing authorization” (MA):

- Erlotinib (in tablet)

- Bevacizumab (in injection)

- Gefitinib (in tablet)

These molecules can be marketed under different names.

Targeted therapies can be used for the management of Stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in combination with chemotherapy. This use should be discussed in CPR according to certain criteria including the histological type of the tumor, its radiological presentation (i.e. where it is located in the lung), its extension and the general state of the patient’s health.

Indications

As part of the management of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a targeted therapy molecule may be combined with chemotherapy.

This possibility should be discussed in CPR, based on certain criteria including the histological type of the tumor, its radiological presentation (i.e., how it is located in the lung), its extent and the general state of the patient’s health.

Types of currently used targeted therapies

The drugs most often used as a targeted treatment for NSCLC are:

- Erlotinib (Tarceva®)

- Bevacizumab (Avastin®)

- Gefitinib (Iressa®)

Erlotinib

Erlotinib is a drug that targets a protein on the surface of cells called the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which participates in the development of cancer cells.

This treatment is called EGFR growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor and is in the form of tablets.

Erlotinib is given alone.

In recent studies, it has been observed that erlotinib can reduce the size of tumors in approximately one in ten patients and help patients feel better.

It is proposed to treat cancer that has not reacted to at least one chemotherapy. This is why it is given as a second- or third-line treatment.

Bevacizumab

A tumor forms new blood vessels to feed and grow. Bevacizumab, a “humanized” monoclonal antibody, prevents the formation of these blood vessels.

Bevacizumab is given intravenously in combination with chemotherapy for certain types of cancer.

Bevacizumab increases the risk of bleeding, it is not prescribed to people with squamous cell carcinoma because this type of tumor more often causes bleeding due to its central location and tendency to necrosis.

In general, precautions for use are necessary for people who are at risk of bleeding (e.g. bloody sputum, taking anticoagulants).

Gefitinib

Gefitinib is used in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic forms of non-small cell lung cancer. It is in tablet form and is used for patients whose cancer cells have a particular genetic mutation that leads to activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and its receptor (EGFR) which is located on the surface of cells are known for their involvement in the growth and proliferation of normal but also cancerous cells. A mutation has been identified for cancer cells of non-small cell lung cancers; it leads to the activation of the receptor (EGFR) and thus to the stimulation of cell proliferation.

Gefitinib is an inhibitor of this receptor, in other words, it helps to slow the proliferation of cancer cells.

The principle

Treatments for lung cancer are aimed at eliminating the tumor and reducing the risk of cancer returning locally or developing distant metastases.

Once cancer treatment is complete, follow-up is done regularly to:

- Monitor the treatment response of the treated person

- Identify any long-term or late side effects

- Monitor the general well-being of the treated person

- Check for any new symptoms

- Check for signs of recurrence of cancer

- Monitor the lack of development of a second cancer

Appointments are scheduled with the specialist who has followed you. Your doctor is also a privileged interlocutor.

The risk of relapse is highly variable and closely related to the stage of cancer progression at the time of diagnosis and the continuation or discontinuation of smoking.

Most recurrences of lung cancer occur within two years of treatment.

However, these recurrences can occur much later.

Monitoring can detect a relapse. A new treatment is then put in place.

This monitoring is also necessary to prevent and treat possible side effects.

Side effects depend on the treatments received, the doses administered, the type of cancer and how the patient and his / her body have responded to the disease and treatments. They do not appear systematically.

The doctor can put the patient in contact with professionals (nurses, social workers, masseurs-physiotherapists, psychiatrists or psychologists, etc.) or associations of former patients.

These professionals and associations can help the patient return to normal life. In France, there are the best specialists for such situations.

In case of cancer recurrence

When there is a recurrence of lung cancer, it means that it has reappeared after being treated.

It can reappear in the same place as the initial tumor (local recurrence), in the same region (locoregional recurrence) or recur in another part of the body.

Treatment of a recipient of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

The treatment that will be proposed is always discussed in multidisciplinary consultation meetings (RCP).

Chemotherapy is prescribed most often. Surgery can be discussed according to the possibility of resectability and operability of the patient. A single metastasis can sometimes be operated.

The use of radiotherapy may be considered depending on the previous treatment and doses already administered.

It is also possible to administer cerebral or bone radiotherapy, always according to the doses already delivered to the patient.

Treatment of a recipient of small cell lung cancer (SCLC)

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is again proposed in the case of a recurrence of small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

If cancer recurs more than three months after the initial treatment, it is possible to repeat the same chemotherapy protocol.

Radiotherapy

The use of radiotherapy in the case of recurrent SCLC can be considered depending on the previous treatment and doses already administered.

It is also possible to administer cerebrally or bone radiotherapy, always according to the doses already delivered to the patient.